Farming is a hard way of life, without question. No matter how skilled and proficient the farmer, things do go wrong and accidents happen. Losing livestock, disease and illness is all part of the job. Animals can become ill and then die. The role of the large animal vet may be crucial in saving a life. Dick’s pedigree young bulls often sold very well at the breed society sales at Carlisle and Perth. In recent years Dick had bred a National Junior Champion and was a very respected producer within the breed. In the yard I fed and looked after three cracking young lads that were due to be sold the following autumn. Sometimes in winter they were let out of the sheds in to the open yard to feed and exercise.

One morning I arrived down to the yard pushing the usual barrow load of silage and I noticed one of the bulls clearly in distress and looking very bloated. Quickly I ran back up to the main yard to find Benson who did most of the show preparation work on the bulls. The bull had an intestinal blockage and a vet was summoned immediately. I continued with my chores.

Sometime later I arrived back at the yard to find that the vet had no option but to perform an operation in order to release the gases that had become trapped in the bull’s stomach. I watched in fascination as the young vet worked away to insert a valve called a cannula through the animals side in order to insert a tube in to the stomach. Eventually the vet managed to puncture the stomach and then dive for cover as the contents of the bulls stomach erupted from the tube like a geyser. It was the foulest stench I had ever smelt. The relief on the bulls face was immediate. Sadly the cannula had to stay as this problem recurred. I even had to open the valve myself some mornings, careful always to get out of the way. The cause of the problem was ingestion of dead oak leaves, the result eventually was that the bull had to be sold in to the meat chain rather than enjoy a long and happy life as a breeding bull. This event was one of many disappointments in the year that all farmers have to put up with.

Generally working with the pedigree Charolais cattle was good fun. One day in summer up at the Pardshaw land we were touring the Charolais cattle in the Land Rover. Dick had a huge Charolais stock bull called Chesholm Newtown. By all accounts he was very friendly, in fact too friendly. As we drove past him, he started to move towards the Land Rover head down. Dick advised me in no uncertain terms that I should drive the Land Rover out of his way.

I knew better than to argue. Benson told me later that Dick had been driving through the field on his own one day and the bull had decided to have some fun with the Land Rover. At over 1400 kgs, he had nearly turned the vehicle over even though he was just playing! I always kept my eye on Newtown, from that day forward.

By August my placement was coming to an end. I had learned very much about good stocksmanship and a fair bit about myself too. I was well over two stones lighter than when I started. Many times I had gone to bed deciding to pack in and not go back. Every morning I went back for more.

My last morning of employment was to be Saturday 4th of August. It was the day of Cockermouth Show, the local agricultural show. The Clark team were proudly showing a bit of everything. They had dairy cattle, Charolais cattle and mule lambs. Each entry was top class and produced to perfection. In order to buy everyone some time and to ensure my last morning went smoothly, I arrived down at the farm half an hour early. No one else was up and about.

In the cool, still morning air I walked down to the far cow pastures, admiring the new post and wire fences I had helped to put up right through Easter Weekend. Then I gathered up the milk cows that were happily chewing their cud or grazing. Slowly but surely I walked them back to the farm, along the mosses, through the wet morning dew alongside the dry stone wall that Dick had taught me how to gap up. I knew many by name and was able to walk alongside them giving them a pat or a stroke as we went. Old Twinkle with her huge udder waddled along at the back with me resting my hand on her as she went.

On the banks above the cow pasture i could see St Michaels Chapel at the northern boundary of Mosser Mains Farm. Adam De Mosser cleared these lands to farm in the 13th century. Now for just a few short months 700 years later another Adam had worked on the land, learning skills and experience to last a lifetime.

Back at the farm Twinkle had pushed her way through the collecting yard up to the parlour door. First in as always. By the time Alan turned out to start milking, the parlour was set up correctly, the bulk tank connected and all filters in the right place.

Milking was soon through but there was no time for breakfast as the beautifully cleaned and prepared show animals were loaded in to well- strawed trailers to head for the show field. With a wave goodbye, I was left standing in the yard alone. The job was over and done. Was I sad? No not at all. Was I satisfied? Yes quietly away and quite relieved. With a deep breath and a last look around the yard, I headed for home with a growing realisation that within the month I would be leaving my family and heading a long way south to Cirencester and on to the next chapter of my life.

I hope I have not created too harsh a picture of Dick Clark. He was hard on me and he pushed me like never before or since, but run or run faster can be a good way of working at the right time.

To bring this tale full circle, we have to jump forward five years. It is 1991. I am 26 years old. Three years out of college I have made it back to Cumbria and I have been steadily learning my new trade as an auctioneer at Penrith, Lazonby and Troutbeck. The time has arrived when I am now selling at bigger and better sales.

It is Lazonby auction in the autumn. The prestigious autumn sale of Registered Blue Faced Leicester Ram Lambs is upon us. I am told that I will be second auctioneer on the rostrum. This sale is the cream of the crop. The hierarchy of the Leicester Breeders will be here buying and selling. I did sell some shearling and older tups last year with mixed results (another story), but now this is the big time.

A line is drawn in the catalogue where I am to start selling. The second consignment I will sell is from Dick Clark, Mosser Mains. I go down to the pens to talk to him and other vendors, to see if they have any instructions for me. Dick is busy talking to potential buyers who are looking at his sheep. So I keep out of the way.

Back at the ring my nerves grow and grow. I question myself constantly. Am I good enough to do this? Why am I even here? It is too late now and before I know it the microphone is being handed to me. I take a deep breath, pick up the gavel, and the room is mine.

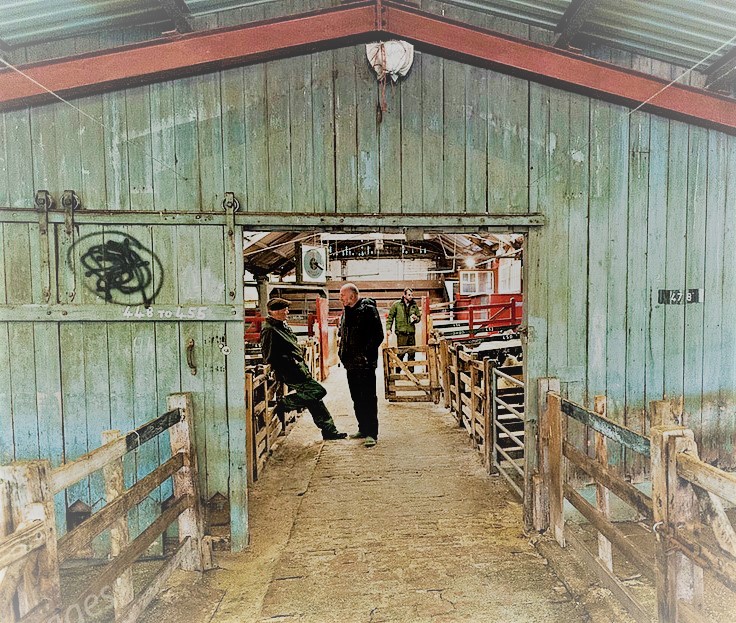

I sell the first vendors only ram easily and immediately Dick and Alan Clark are walking through the big oak double doors behind their very nice Leicester Shearling Ram. Despite the fact that Dick shouted at me many times at Mosser Mains, he is actually very quietly spoken. I listen very hard as he whispers in my ear. “This should make 1100 guineas”. It is not a reserve, it is just Dick valuing his own stock. I trust him and I know him. He’s never far wrong!

I get in to gear and move quickly through the bids. Soon I am bring the hammer down at exactly 1100 guineas. Unbelievable! I sell the rest of his consignment and before I know it Dick and Alan are saying thank you and walking out of the ring. There is no time to think though. The sale goes on. After half an hour I realise I am enjoying it and in the swing. With a little prompting from the senior auctioneers who take it in turns to sit with me, I get through my stint. It is over in a flash and I am handing the microphone back. Quietly I move to the back of the rostrum and then it hits me. The first proper consignment of Blue Faced Leicester’s that I sell at Lazonby is from Dick Clark, Mosser Mains Farm. It seems entirely fitting to me.

The following year, following Peter Sarjeant’s retirement, I am now to be the weekly dairy auctioneer at Penrith. It is my first day on the job, a Tuesday morning. As always I am beyond nervous. Can I really do this? What do I know about dairy cows?

The first cows for sale arrive at the unloading docks. Low and behold it is Dick Clark, bringing a very tidy newly calved heifer for sale. He often does sell at Penrith and has a good following. He is first in to the ring and the thought is not lost on me that yet again the first time I sell in a particular sales ring, it is for Dick Clark.

I lean down low as he whispers to me “She’ll make over £1000”.

I’ve no need to do anything other than take bids. Dick’s dairy cattle are popular and always sell well. Even so I take my time. Learned men in the trade have told me never to rush selling a dairy cow. It is not like selling prime cattle to professional buyers. Farmers are often reluctant or shy bidders if they are not used to it, or don’t really like spending their own money. A good auctioneer can work the room, cajole another bid, work the buyers to go that extra few pounds. Much as my instinct is to get the hammer down, I keep trying, imploring another bid from a man shaking his head then laughing at me as I crack a feeble joke. It works though, as he nods his head at me, having one last shot at buying the heifer.

The hammer comes down. Dick is dead pan. He is never going to show publicly that he is pleased with the price, but at £1050 I have done my job well. He politely thanks me and walks out of the ring. A while later I see Dick in the auction foyer. “I’ll have another for next week” he tells me. That’s all the praise I need.

A few years later I’ve moved on and I am going through a wobbly patch in the old auction at Cockermouth. The pressure is on the company. We aren’t making much money, we’ve had some bad debt, and the stock numbers aren’t great. The directors are putting me under pressure. I’m finding it tough. They get frustrated with me and quite honestly it won’t be the last time in my career. I get it right quite a lot of the time but in the words of Dick Clark, I usually manage to bugger it up somewhere down the line. Nobody’s perfect but as I go through my career, I find it difficult to back away from what I believe is right. Colleagues will tell me in future, just swallow your pride and do it the way the directors want you to. I sometimes find that hard to do if I don’t agree. It is a failing of mine- perhaps.

One night I jump in the car and drive to Mosser Mains. I need some wise council. Dick will give it to me straight. I have a small whisky with him. He tells me what I need to do. “Stick to your guns, believe in yourself but at this point in time…. don’t run so fast! The jobs going alright really. The main thing is to keep your head down and get stock in to the market, nothing else matters”.

I feel better having talked it through and I am sure that Dick will make his views known to some of the directors. Within the year the market is full of sheep week after week. It keeps the company afloat as we struggle to get planning permission for a new market. I continue to sell stock from Mosser Mains year upon year.

Several years later, in the new market at Cockermouth, the sad news comes through that Dick Clark has passed away. It is a blessing as he has been steadily failing health for a while. Alyson his youngest daughter lives in Eaglesfield with James, our yard foreman. She works in the café at the mart. We are like family. Lyn, their other sister lives in Canada and we don’t see her so often.

I receive word from Alison that Dick’s widow Liz would like to see me at Mosser Mains. I travel up to the farm with a sense of foreboding. Will this be difficult? It isn’t. Some of the family are there and we have a brew and talk about Dick and the time I worked for them and also about other people that have worked for them over the years for I wasn’t the only one to be educated there. Liz tells me that they would like me to offer a eulogy within the funeral service. They tell me some stories they would like me to include together with some of my own.

I am honoured and very proud to be asked. The service is a celebration of Dick’s farming life. I recount the “you always manage to bugger it up” tale and also about selling the Leicester’s and the dairy cows. He was I tell them, a man of extra- ordinary self-belief and confidence. A brilliant stock man and judge of cattle and sheep, but for all of that, not an easy man to work with, or for! I am told later that the eulogy summed up Dick very well. It is my final job done for Dick, a farmer and a friend who has featured so much in my career.

After 16 years good years I am leaving Mitchell’s. There is an exciting opportunity to join North West Auctions and build a new mart near Kendal. They want me for my experience and they have also employed my father as the architect. This will be the second time we have worked together on a new mart premises. It will also be the last.

It is not a difficult decision to leave Cockermouth. The new executive Chairman is introducing major changes to the business and we don’t see eye to eye in some matters. The best option for me is to move on and at this moment in time, I am in a position to do so. I leave without an ounce of regret, job done. Others will take my place no problem. No one is irreplaceable in this world. I truly believe that everything happens for a reason. As one door closes another door usually opens.

Soon a letter arrives in the post from Liz Clark. Much of the letter will remain private but in the final paragraph she says: –

“Mitchell’s new auction was your baby. You brought it to where it is today…. You have given your all to Mitchell’s.

When you worked for Dick I used to think every night- Adam won’t be back in the morning. But you never failed to turn up for work and I think that’s when you became a man”!

I keep the letter in a safe place………